Insights

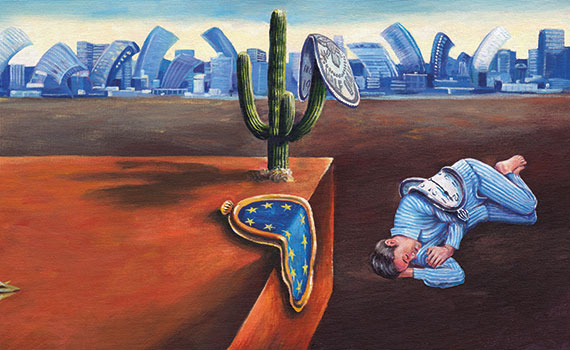

Brexit and the Trump factor are just two of the concerns that will be keeping global CFOs awake in 2017. Ramona Dzinkowski looks at what could be a turbulent year

This article was first published in the January 2017 international edition of Accounting and Business magazine.

The global economic growth story in 2017 is more of the same – slow and steady, with no sudden movements – or so most economists forecasted in October 2016.

World economic output is expected to rise by 3.4% during the course of the next year, and the growth in advanced markets will probably be slower, but stable. Emerging and developing Asia will chug away at 6.3% and is expected to remain on that path for the next four years. Output in the US will rise by 1.8%, on a par with other advanced economies, although Japan will continue to struggle on at a rate of 0.6%.

Growth in Latin America is expected to get back on track following a four-year decline as a consequence of soft commodity prices. Those commodity prices created recessionary pressures across the board and are expected to turn around somewhat in 2017.

However, the ongoing uncertainty plaguing European markets will push eurozone growth rates below world benchmarks, with GDP rising by 1.5% in 2017. In the wake of Brexit, a Duke University CFO survey showed that an overwhelming majority (69%) of European CFOs rated the elevated level of political uncertainty as a ‘large’ or ‘moderate’ risk. The result is that EU CFOs say their companies will be more cautious in capital spending (58%), hiring (49%) and making acquisitions (38%). In September 2016, almost a third of those CFOs indicated that if the UK leaves the EU, their companies will shift production and or/operations towards the rest of Europe.

Brexit: not bothered

Outside the EU, the Brexit vote didn’t have much of an impact on how most companies will be operating in 2017. According to ACCA’s Q3 global economic conditions survey of accounting professionals around the world, 70% of North American respondents think there will be no impact on their companies from the Brexit vote – a relatively small portion of US exports go to the UK.

Similarly, for the biggest global players, a wholesale change in strategy with respect to the UK, and specifically England, doesn’t appear to be on the cards. In fact, according to a recent CNBC survey of 48 CFOs from some of the world’s largest companies, 70% say there is no change in their perspective on the likelihood of their doing business in the UK.

Alex Eng, CFO of EDF Renewable Energy, a US-based subsidiary of French company EDF Energies Nouvelles, is typical. He expresses little concern for the Fortune 100, pointing to the robust risk management practices within his company and others like it. ‘Certainly,’ he says, ‘with many companies like EDF, which are strong global Fortune 100 companies, we have responsive and agile risk mitigation strategies. We have business review policies and procedures that are robust enough to weather a lot of these geopolitical events. I think for most of us around the world, with or without direct investments in the UK, geopolitical events have become almost a part of everyday life. That’s what being in business is all about. For strong global companies, Brexit will come, Brexit will go, and those companies will still be here.’

But not all companies are created equal when it comes to the Brexit effect on their prospects for 2017. To date, some companies have reacted quite decisively to the changing risk outlook and uncertainty.

As Stephen Smyth ACCA, CFO of Brookfield Financial, a global investment bank headquartered in Toronto with UK interests, explains, it’s the real estate sector that’s feeling the immediate impact of a potential UK secession from the EU. ‘Values are a key concern, certainly in the UK market,’ he says, » ‘and with respect to high-profile real estate funds, blocks on redemptions are creating liquidity issues. The liquidity in the market is such that you’re being locked into assets because there’s no activity; there’s no transactional activity [so] if you want to get out of it, you can’t – certainly not at a price that makes sense. So it becomes a difficult situation.’ Immediately after the Brexit vote, Canada Life Financial, an insurance and wealth management company with significant exposure in the region, promptly suspended trading of its UK property funds, a portfolio valued at £500m.

The longer-term impact is hard to predict at this stage, says Smyth. ‘Some fund managers are saying they’ve already marked down the value of the buildings they own – usually office buildings – by 4.5% to 5%. That’s not a good sign of things to come. Worst-case projections: office values could fall by as much as 20% within three years of the country leaving the EU, and that will certainly impact a company’s ability to refinance.’

For Brookfield Financial and many others, a prolonged decline in the value of sterling will definitely hit their bottom line. ‘Europe is one of our largest regions, so in terms of revenue, a sustained decline in sterling in 2017 would obviously be detrimental,’ Smyth explains. ‘When that region’s results are consolidated, it’s obviously expressed in our functional currency, which is US dollars. So that’s a concern. At the same time a lot of our European deals are denominated in euro currency and I think what’s bad news for sterling is not going to be good news for the euro. They’ll probably move pretty much in tandem.’

Trump effect

While the consequences of Brexit are still on the minds of many, a bigger cause for concern for CFOs in 2017 is the most recent political upset in the US. On 9 November, following the US election, much of what we expected about how the global economy was going to behave in 2017 was turned on its head. After a knee-jerk negative reaction, the markets turned around with irrational exuberance in the hope that Trump’s election will give the US economy a Keynesian kick in the pants. Bond yields on US treasuries jumped, along with the value of the US dollar against international currencies.

However, what was good news for the US market was bad news for many other parts of the world. For example, Trump’s promise to unravel the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has had a particularly unsettling effect on Latin American currencies. Immediately after the US election, the peso lost 15% of its value against the US dollar, trading at 20.5:1 on the morning of 9 November compared with 18.6:1 on 7 November.

The possibility of weaker private consumption and lower fixed investments due to potential trade restrictions will also be particularly detrimental to the Mexican economy, the region’s powerhouse, and are likely to derail any hope of the country achieving its 2.3% growth target in 2017.

No big strategic moves

While the equity markets may be quick to respond to pretty much any news these days, CFOs are making no big strategic moves just yet. Uncertainty around potential trade restrictions, the future of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Dodd-Frank, the Offshoring Act, the Affordable Care Act and NAFTA are all in question. 2017 will be a time for many CFOs to re-examine their strategies under various risk scenarios. Some will be focusing on investment, cash and liquidity issues, with expectations of higher interest rates; others, particularly in the construction and materials sector, will be anxiously looking forward to a sales boost from the injection of infrastructure cash.

Deflating regional currencies

Companies with interests in China and Latin America will be re-evaluating any expansion plans they have, along with their hedging strategies in the wake of deflating regional currencies. For Julian Leung, CFO at Chinese textile manufacturer Yongsheng Advanced Materials Company, the volatility in the renminbi will be keeping him up at night in 2017. Some of his costs are exposed to the strong US dollar, and ‘the path of the RMB is what we talk about every day,’ he comments. ‘The uncertainty around US policy towards China has made it challenging for us to make investment decisions and there is little if anything we can do to plan. It’s difficult to predict and think about how to proceed with your hedging strategies.’

Meanwhile, large and small Chinese companies alike whose products are destined primarily for the US market are seriously worried about the possibility of the new US administration slapping a 45% tariff on manufactured imports – the US accounts for around US$500bn of Chinese exports a year.

Many CFOs in China are hoping the Trump administration will ultimately prove pragmatic. Leung points out: ‘US trade with China is a two-way street. Taxing Chinese imports will increase the business costs in the US, making them less profitable and less efficient. This would limit the US’s ability to grow, and will have a negative impact on employment, particularly in the manufacturing sector.’

Ramona Dzinkowski is a Canadian economist and editor-in-chief of the Sustainable Accounting Review

Insights

"The uncertainty around US policy towards China has made it very difficult for us to make investment decisions"