All about stakeholders – part 1

This article introduces the idea of stakeholders and stakeholding. It starts with definitions of the relevant terms, explains the nature of stakeholder ‘claims’, and then goes on to use the Mendelow framework to explain how stakeholding is linked to influence. Finally, it covers the different ways in which stakeholders are categorised and how they are distinguished from each other.

Definitions and examples

The subject of stakeholders features in the Strategic Business Leader (SBL) syllabus. It is central to any understanding of the subject of business and organisational ethics. The purpose of this article is to bring all aspects of the subject together so that students new to the field can gain an understanding of what the subject means and how it is constructed as far as ethics is concerned.

Any definition of a stakeholder must take into account the stakeholder–organisation relationship. The best definition of this is by Freeman, who in 1984 defined a stakeholder as: ‘Any group or individual who can affect or [be] affected by the achievement of an organisation’s objectives’. This definition shows the important bi-directionality of stakeholders – that they can be both affected by – and can affect – an organisation. Of course, some stakeholders will be in both camps.

When we think of stakeholders, it is possible to list many examples, but the ones that usually come to mind are shareholders, management, employees, trade unions, customers, suppliers, and communities. However, larger and more complex organisations can have many more stakeholders than these. Compare, for example, the different complexities of a small organisation, such as a corner shop or street trader, with a large international organisation such as a major university or ACCA. The first important aspect of stakeholder theory is, therefore, to recognise that stakeholders exist and that the complexity and range of stakeholders relevant to an organisation will depend on that organisation’s size and activities.

Stakeholder 'claims'

The reason why stakeholders are important in both business ethics and in strategic analysis is because of the notion of stakeholder ‘claims’. A stakeholder does not simply exist (as far as the organisation is concerned) but makes demands of it. This is where understanding stakeholding can become more complicated.

Essentially, stakeholders ‘want something’ from an organisation. Some want stakeholders to influence what the organisation does (those stakeholders who want to affect) and others are, or potentially could be, concerned with the way they are affected by the organisation and may want to increase, decrease, or change the way the activities of the organisation affect them. One of the problems with identifying stakeholder claims, however, is that some stakeholders may not even know that they have a claim against an organisation or may know they have a claim but are unaware of what it is. This brings us to the issue of direct and indirect stakeholder claims.

Direct stakeholder claims are made by those with their own ‘voice’. These claims are usually unambiguous and are often made directly between the stakeholder and the organisation. Stakeholders making direct claims will typically include trade unions, shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and, in some instances, local communities.

Indirect claims are made by those stakeholders unable to make the claim directly because they are, for some reason, inarticulate or ‘voiceless’. Although this means they are unable to express their claim direct to the organisation, it is important to realise that this does not invalidate their claim. Typical reasons for this lack of expression include the stakeholder being (apparently) powerless (eg an individual customer of a very large organisation), not existing yet (eg future generations), having no voice (eg the natural environment), or being remote from the organisation (eg producer groups in distant countries). This raises the problem of interpretation. The claim of an indirect stakeholder must be interpreted by someone else in order to be expressed, and it is this interpretation that makes indirect representation problematic. How do you interpret, for example, the needs of the environment or future generations? What would they say to an organisation that affects them if they could speak? To what extent, for example, are environmental pressure groups reliable interpreters of the needs (claims) of the natural environment? To what extent are terrorists reliable interpreters of the claims of the causes and communities they purport to represent? This lack of clarity on the reliability of spokespersons for these stakeholders makes it very difficult to operationalise (to include in a decision-making process) their claims.

Understanding the influence of each stakeholder (Mendelow)

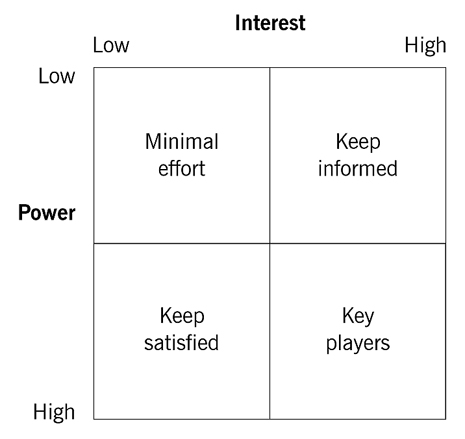

In strategic analysis, the Mendelow framework is often used to attempt to understand the influence that each stakeholder has over an organisation’s objectives and/or strategy. The idea is to establish which stakeholders have the most influence by estimating each stakeholder’s individual power over – and interest in – the organisation’s affairs. The stakeholders with the highest combination of power and interest are likely to be those with the most actual influence over objectives. Power is the stakeholder’s ability to influence objectives (how much they can), while interest is the stakeholder’s willingness (how much they care).

Influence = Power x Interest

There are issues with this approach, however. Although it is a useful basic framework for understanding which stakeholders are likely to be the most influential, it is very hard to find ways of effectively measuring each stakeholder’s power and interest. The ‘map’ generated by the analysis of power and interest (on which stakeholders are plotted accordingly) is not static; changing events can mean that stakeholders can move around the map with consequent changes to the list of the most influential stakeholders in an organisation.

The organisation’s strategy for relating to each stakeholder is determined by the part of the map the stakeholder is in. Those with neither interest nor power (top left) can, according to the framework, be largely ignored, although this does not take into account any moral or ethical considerations. It is simply the stance to take if strategic positioning is the most important objective. Those in the bottom right are the high-interest and high-power stakeholders, and are, by that very fact, the stakeholders with the highest influence. The question here is how many competing stakeholders reside in that quadrant of the map. If there is only one (eg management) then there is unlikely to be any conflict in a given decision-making situation. If there are several and they disagree on the way forward, there are likely to be difficulties in decision making and ambiguity over strategic direction.

Stakeholders with high interest (ie they care a lot) but low power can increase their overall influence by forming coalitions with other stakeholders in order to exert a greater pressure and thereby make themselves more powerful. By moving downwards on the map, because their power has increased by the formation of a coalition, their overall influence is increased. The management strategy for dealing with these stakeholders is to ‘keep informed’.

Finally, those in the bottom left of the map are those with high power but low interest. All these stakeholders need to do to become influential is to re-awaken their interest. This will move them across to the right and into the high influence sector, and so the management strategy for these stakeholders is to ‘keep satisfied’.

Figure 1 - The Mendelow Framework

Figure 1 - The Mendelow Framework

How to categorise stakeholders

There are a number of different ways of distinguishing one type of stakeholder in an organisation from another:

1. Internal and external stakeholders

Perhaps the easiest and most straightforward distinction is between stakeholders inside the organisation and those outside. Internal stakeholders will typically include employees and management, whereas external stakeholders will include customers, competitors, suppliers, and so on. Some stakeholders will be more difficult to categorise, such as trade unions that may have elements of both internal and external membership.

2. Narrow and wide stakeholders (Evans and Freeman)

Narrow stakeholders are those that are the most affected by the organisation’s policies and will usually include shareholders, management, employees, suppliers, and customers who are dependent upon the organisation’s output. Wider stakeholders are those less affected and may typically include government, less-dependent customers, the wider community (as opposed to the local community) and other peripheral groups. The Evans and Freeman model may lead some to conclude that an organisation has a higher degree of responsibility and accountability to its narrower stakeholders.

3. Primary and secondary stakeholders (Clarkson)

According to Clarkson: ‘A primary stakeholder group is one without whose continuing participation the corporation cannot survive as a going concern’. Hence, whereas Evans and Freeman view stakeholders as being (or not being) influenced by an organisation, Clarkson sees the important distinction as being between those that do influence an organisation and those that do not. Secondary stakeholders are those that the organisation does not directly depend upon for its immediate survival.

4. Active and passive stakeholders (Mahoney)

Mahoney (1994) divided stakeholders into those who are active and those who are passive. Active stakeholders are those who seek to participate in the organisation’s activities. These stakeholders may or may not be a part of the organisation’s formal structure. Management and employees obviously fall into this active category, but so may some parties from outside an organisation, such as regulators (in the case of, say, UK privatised utilities) and environmental pressure groups.

Passive stakeholders, in contrast, are those who do not normally seek to participate in an organisation’s policy making. This is not to say that passive stakeholders are any less interested or less powerful, but they do not seek to take an active part in the organisation’s strategy. Passive stakeholders will normally include most shareholders, government, and local communities.

5. Voluntary and involuntary stakeholders

This distinction describes those stakeholders who engage with the organisation voluntarily and those who become stakeholders involuntarily. Voluntary stakeholders will include, for example, employees with transferable skills (who could work elsewhere), most customers, suppliers, and shareholders. Some stakeholders, however, do not choose to be stakeholders but are so nevertheless. Involuntary stakeholders include those affected by the activities of large organisations, local communities and ‘neighbours’, the natural environment, future generations, and most competitors.

6. Legitimate and illegitimate stakeholders

This is one of the more difficult categorisations to make, as a stakeholder’s legitimacy depends on your viewpoint (one person’s ‘terrorist’, for example, is another’s ‘freedom fighter’). While those with an active economic relationship with an organisation will almost always be considered legitimate, others that make claims without such a link, or that have no mandate to make a claim, will be considered illegitimate by some. This means that there is no possible case for taking their views into account when making decisions.

While terrorists will usually be considered illegitimate, there is more debate on the legitimacy of the claims of lobby groups, campaigning organisations, and non-governmental/charitable organisations.

7. Recognised and unrecognised (by the organisation) stakeholders

The categorisation by recognition follows on from the debate over legitimacy. If an organisation considers a stakeholder’s claim to be illegitimate, it is likely that its claim will not be recognised. This means the stakeholder’s claim will not be taken into account when the organisation makes decisions.

8. Known about and unknown stakeholders

Finally, some stakeholders are known about by the organisation in question and others are not. This means, of course, that it is very difficult to recognise whether the claims of unknown stakeholders (eg nameless sea creatures, undiscovered species, communities in close proximity to overseas suppliers, etc) are considered legitimate or not. Some say that it is a moral duty for organisations to seek out all possible stakeholders before a decision is taken and this can sometimes result in the adoption of minimum impact policies.

For example, even though the exact identity of a nameless sea creature is not known, it might still be logical to assume that low emissions can normally be better for such creatures than high emissions.

Adapted and updated for SBL from an article originally written by a member of the P1 examining team