In the Advanced Performance Management exam, you could be asked to evaluate the performance of not-for-profit organisations (for example, public sector organisations) as well as profit-seeking ones.

This article discusses the concept of value for money, and how it can be used to measure performance in not-for-profit organisations. The article uses a past exam question (from the September/December published sample questions) to illustrate this. The scenario from the exam question is summarised in the article, but it is essential to read the scenario and requirement in full and keep these to hand while reading the article.

The importance of value for money (VFM)

A key theme in contemporary performance management is that organisations need to measure, and manage, non-financial aspects of performance, rather than focusing solely on financial aspects. However, in profit-seeking organisations, there remains an underlying financial objective: typically, to maximise profit in order to maximise value for shareholders.

By definition though not-for-profit organisations do not have this underlying objective. Nonetheless, financial performance remains important in not-for-profit organisations (for example, comparing actual expenditure against budget, or comparing the surplus (or deficit) of income over expenditure.

However, these organisations also need to monitor how efficiently they are using the resources available to them, and how well they are performing in relation to their key objectives. For example, for hospitals and medical centres, how effectively they are providing health care to their patients; for schools and universities, the quality of education they are providing to their students.

In this respect, three important aspects of performance to measure are: economy, efficiency and effectiveness; the so-called ‘three Es’. Achieving these three Es will help an organisation to ensure it is delivering good value for money.

Value for money is seen as an appropriate framework for measuring performance in not-for-profit organisations, because value for money reflects not only the cost of providing a service but also the benefits achieved by providing it. In the absence of an underlying profit motive, assessing the benefits provided by a service is a particularly important part of evaluating its performance: for example, the benefits received by patients from hospital treatment they receive; the quality of education that students receive at their school or college.

Importantly also, value for money is not simply about minimising cost. To use the UK National Audit Office’s definition: “Good value for money is the optimal use of resources to achieve the intended outcomes” where ‘optimal’ means “the most desirable possible given expressed or implied restrictions or constraints”.1

Value for money – the three Es

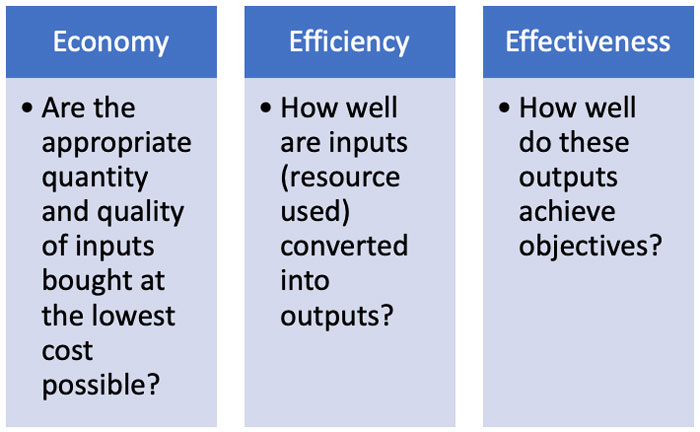

The key to achieving good value for money is finding an appropriate balance between the three Es (as summarised in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Drivers of value for money

Economy: obtaining the appropriate quantity and quality of resources at the lowest cost possible; optimising the resources (inputs) which an organisation has.

Efficiency: maximising the output generated from units of resource used; optimising the process by which inputs are turned into outputs.

Efficiency can often be measured in terms of the cost of providing a service per unit of resource used, per unit of output, or per beneficiary served (in the context of a service).

For example, if the number of teachers employed by two schools is the same, but the first school has twice as many pupils as the second, we could say the first school is more efficient, because the staff costs per pupil will be lower.

Effectiveness: the relationship between the organisation’s intended and actual results (outputs); the extent to which it achieves its objectives.

For example, one of the indicators which is often used to measure schools’ performance is exam results, and this provides a measure of effectiveness. Is the tuition which pupils receive building their knowledge and, in turn, helping them to pass their exams?

Potential conflicts between the three Es

Although the aim of value for money is to achieve an appropriate balance between the three Es, this can often be difficult to achieve. Each of the Es aims to achieve different – potentially conflicting – outcomes in an organisation.

For example, increasing the number of pupils in each class at a school could help to improve efficiency (by reducing staff costs per pupil), but the quality of the pupils’ learning experience might suffer as a result. So, in effect, increasing efficiency could be detrimental to effectiveness.

In recent years, there have been many stories in the news about cost savings or budget cuts in public sector services (health care; education; police forces). These suggest an emphasis on ‘economy’ – and potentially ‘efficiency’ – rather than the ‘effectiveness’ of the services.

However, it is very important to remember that the value for money framework highlights the importance of measuring (and managing) all three Es, rather than focusing just on one aspect of performance.

This also has implications in relation to choosing performance measures. Organisations will need data to assess how well they are achieving value for money, and therefore in order to assess value for money appropriately, the range of performance measures used will need to address all three Es, rather than, for example, focusing primarily on cost (economy) or efficiency.

Equity

Sometimes a fourth ‘E’ is also included when measuring value for money performance: equity.

This reflects the extent to which services are available to, and reach, the people they are intended for, and whether the benefits from the services are distributed fairly.

For example, if an advice service provided to residents by a local authority is provided in a language that some residents do not speak, those residents will not be able to benefit from the service.

Evaluation of VFM from the Section A question published in the September/December 2020 sample questions.

The case study scenario identified that, following a recent change of government, the new minister in charge of policing in the country of Deeland has been instructed to improve the performance of the Deeland Police (DP).

The scenario identified DP’s mission statement – ‘to protect the community and prevent crime while providing a value for money service’ – and four critical success factors (CSFs) which had been proposed to support this:

- Greater protection and more support for those at risk of harm

- Be better at catching criminals

- Reducing the causes of crime by increased involvement with local communities

- Create a task force to develop skills in detection and prosecution of virtual crime.

A table of data was also provided – as replicated below.

Deeland Police data for each year ending 30 June

|

20X5 |

20X4 |

20X3 |

Population of Deeland (‘000s) |

11,880 |

11,761 |

11,644 |

|

|

|

|

Number of police officers |

37,930 |

38,005 |

38,400 |

Number of administrative staff |

12,320 |

12,197 |

12,075 |

Number of crimes reported in the year |

541,735 |

530,900 |

520,282 |

Number of violent crimes reported in the year |

108,347 |

106,180 |

104,056 |

Number of crimes solved in the year |

297,954 |

300,934 |

303,943 |

Number of complaints |

7,624 |

7,512 |

7,483 |

Response to an incident within the allocated time limit |

84% |

86% |

87% |

|

|

|

|

Cost of police force for the year ($m) |

2,248 |

2,226 |

2,203 |

Staff costs (all staff, including police officers) ($m) |

2,026 |

2,103 |

2,141 |

Requirement

The first part of the question focused on CSFs and key performance indicators (KPIs) and included a requirement to provide up to two justified KPIs for each CSF.

Then, the second part – which is the one we will focus on here – asked candidates for an explanation of the 3Es (economy, efficiency and effectiveness) and how this links to the work on CSFs and KPIs. Candidates were also asked to use the data provided to evaluate whether DP provides a value for money service.

The requirement was worth 13 marks.

Tackling the question

As the question asks for an explanation of the 3Es, a sensible starting point would be to give brief definitions of each of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

As we mentioned earlier, effectiveness relates to the extent to which an organisation achieves its objectives and intended results. So, this is an important link to CSFs and KPIs. Having identified its key performance indicators (eg the percentage of crimes solved; reducing the total number of crimes), how effectively has DP achieved these? How has its performance in these areas changed over time?

In this scenario, we are only given data for DP, so we can only assess its own performance over the three years. However, if the data were available, it would also be useful to compare actual performance against targets, and to benchmark DP’s performance against that of other police forces. (Although we don’t discuss league tables in this article, these are often used to benchmark performance in public sector organisations; and another requirement in this exam question looked at the potential introduction of league tables).

Is DP providing a value for money service?

The key part of this question, though, is analysing the data provided and evaluating what this shows about the economy, efficiency and effectiveness of the service DP provides.

Economy

Cost is the key issue here – is DP obtaining appropriate resources at the lowest costs possible? – so the final two rows of data are important.

The overall costs of the police have increased slightly each year. However, staff costs, which make up most DP’s costs, are falling. A positive factor in terms of economy?

The data also gives information about the numbers of police officers and administrative staff, and this shows that the number of police officers has been falling while the number of administrative staff has increased.

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of police officers | 37,930 | 38,005 | 38,400 |

| Number of administrative staff | 12,320 | 12,197 | 12,075 |

| Total number of staff | 50,250 | 50,202 | 50,475 |

| % of staff who are officers | 75.5% | 75.7% | 76.1% |

| Staff costs ($m) | 2,026 | 2,103 | 2,141 |

| Cost per employee | 40,318 | 41,891 | 42,417 |

Again, this could be a positive factor in terms of economy, if DP is recruiting cheaper administrative staff to do jobs previously carried out by police officers. Remember our definition of economy: “obtaining the appropriate quantity and quality of resources at the lowest cost possible”. If certain aspects of the work can be done by administrative staff, why pay more to have them done by a police officer?

Efficiency

As we have mentioned earlier, a key aspect of efficiency is output per unit of resource.

We have looked at staff costs in the context of economy, but as a measure of efficiency we could look at the number of police officers relative to the population of Deeland. (The logic here being the more people served per police officer, the more efficient the police officers are.)

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population of Deeland ('000) | 11,880 | 11,761 | 11,644 |

| Number of police officers | 37,930 | 38,005 | 38,400 |

| People per police office | 313.2 | 309.5 | 303.2 |

| Number of police officers per '000 people | 3.19 | 3.23 | 3.30 |

So, on this basis, it might seem that reducing the number of police officers has helped to improve efficiency as well as economy.

But what about DP’s efficiency in terms of solving crimes? We know the number of crimes solved each year, and we know the numbers of staff, so we can calculate the number of crimes solved per police officer or per employee as a key measure of efficiency.

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of crimes solved in the year | 297,954 | 300,934 | 303,943 |

| Number of police officers | 37,930 | 38,005 | 38,400 |

| Total number of staff (officers + administrative staff) | 50,250 | 50,202 | 50,475 |

| Crimes solved per police officer | 7.86 | 7.92 | 7.92 |

| Crimes solved per employee | 5.93 | 5.99 | 6.02 |

Whichever measure is used (crimes solved per police officer, or per employee) the number of crimes solved is falling, and therefore DP’s performance in this respect is worsening.

So, this raises the possible concern that although reducing the numbers of police officers and changing the mix of staff has reduced costs (and improved ‘economy’) it has reduced efficiency. This concern is also reinforced by the fall in the percentage of incidents which DP responds to within the allocated time limit.

And what impact has the reduction in the number of police officers had on DP’s effectiveness?

Effectiveness

As we have already mentioned, effectiveness relates to how well an organisation is performing in relation to its objectives or goals. So, in this scenario, the issue is: how well is DP performing against its CSFs (and the related KPIs)?

The data provided doesn’t allow us to assess DP’s performance against all its CSFs (for example, there is no data about virtual (or cyber) crimes), but there are still some useful measures we can calculate:

Protecting those at risk

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of violent crimes | 108,347 | 106,180 | 104,056 |

| % change year on year | 2.04% | 2.04% | |

| Number of violent crimes per 1,000 population | 9.12 | 9.03 | 8.94 |

| % change year on year | 1.02% | 1.03% |

Be better at catching criminals

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of crimes reported in the year | 541,735 | 530,900 | 520,282 |

| Number of crimes solved in the year | 297,954 | 300,934 | 303,943 |

| % clear-up rate in solving reported crimes | 55.0% | 56.7% | 58.4% |

These figures are particularly stark in showing the DP is becoming less effective, because while the number of crimes reported is increasing each year, the number of crimes solved has fallen.

Reduce the causes of crime

| 20X5 | 20X4 | 20X3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of crimes reported | 541,735 | 530,900 | 520,282 |

| % change | 2.04% | 2.04% |

The logic behind the CSF here would appear to be ‘prevention rather than cure’. If DP can reduce the causes of crime, this should lead to a reduction in the number of crimes. However, the numbers of reported crimes are increasing.

In each case, the indicators suggest that DP is not performing effectively; with the numbers of crimes increasing, and DP’s rate in solving them falling.

Although we need to be careful not to assume that correlation implies causality, it is nonetheless likely that the reduction in police officer numbers, and the apparent restrictions on staffing costs, have contributed to a decline in DP’s effectiveness.

Conclusion

This question from the September/December published sample questions provides an excellent illustration of the issues which organisations face when trying to achieve value for money; in particular, the potential relationships between the three Es, and the impact that changing of the Es could have on the others.

More generally, an organisation which fails to achieve its principal objectives will not be successful. As such, organisations (and wider stakeholders, such as governments and funding agencies) need to be aware of the danger of becoming too focused on economy or efficiency (or both) to the detriment of effectiveness.

Focusing on the wrong measures – or focusing on one ‘E’ at the expense of the others – can be very damaging to an organisation. So, the challenge in achieving good value for money is how to balance and manage all three Es: being effective in achieving your objectives yet doing so in an economic and efficient manner.

Written by a member of the Advanced Performance Management examining team

Reference:

(1). National Audit Office (n.d.) Value for money, Online.

Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/successful-commissioning/general-principles/value-for-money/